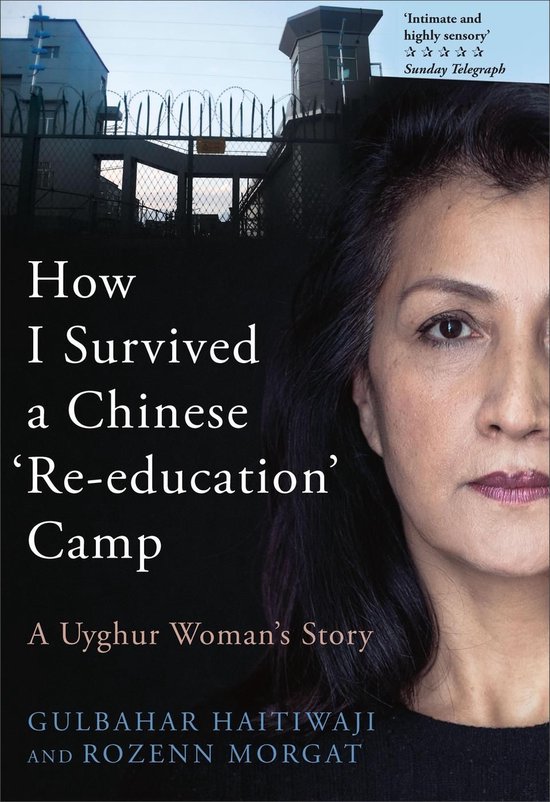

How I Survived A Chinese 'Re-education' Camp - A Uyghur Woma ...

Gulbahar Haitiwaji

- 03 februari 2022

- 9781912454914

Samenvatting:

The First Memoir of China's Internment Camps by a Uyghur Woman

'Moving and devastating' – The Literary Review

'An indispensable account' – Sunday Times

'An intimate, highly sensory self-portrait' – Sunday Telegraph

In November 2016, Uyghur mother and petroleum engineer Gulbahar Haitiwaji answered a routine call from her former company in Xinjiang. "Just paperwork," they said. She flew from Paris to Karamay — and vanished. Her passport was seized; months of interrogations followed; after a year in custody she endured a nine‑minute "trial" without judge or lawyers and was sentenced to seven years in a Chinese "re‑education" camp.

How I Survived a Chinese 'Re‑education' Camp is her lucid, courageous account of what happened next.

From the first cold night in Karamay County Jail, Haitiwaji invites readers into Cell 202, where the lights never dim, cameras never blink, and a wall poster lists rules that forbid speaking Uyghur or praying — while promising a hollow "right to worship." She is chained to a bed for days, fed thin congee and stale bread, and taught how fear erases time. The details are precise and unforgettable, rendered with the restraint of a witness who will not look away.

Transferred to the Baijiantan "school" on the desert outskirts of Karamay, Haitiwaji meets a new, meticulously engineered routine: military drills, silence at meals, and eleven hours a day reciting Communist Party slogans under the watchful portrait of Xi Jinping. The window shutters are bolted; the outside world becomes rumour and memory. One morning, a cellmate named Nadira is simply called by her number and taken away — never to return. In this world of numbered bunks and numbered women, Haitiwaji fights to keep her name.

Beyond the razor wire, her daughter Gulhumar is knocking on doors in Paris — reporters, lawyers, diplomats —refusing to let her mother's story be buried. The book's preface situates Gulbahar's ordeal within Xinjiang's transformation into a surveillance state and the spread of "transformation‑through‑education" camps that would swallow over a million lives, illuminating the machine that ensnared an apolitical mother because of a photo of her child at a peaceful rally.

Written with journalist Rozenn Morgat and translated into English by Edward Gauvin, this memoir balances stark testimony with startling tenderness: a family wedding in Paris before the phone call; a remembered strand of perfume that keeps two bunkmates human; the first phone home after months of silence. Haitiwaji's voice is both intimate and composed—refusing sensationalism, insisting on dignity.

Why you'll love this book

- A rare inside view of a modern indoctrination camp, told by a survivor with an engineer's eye for systems and a mother's heart for people.

- Vivid scenes—being hooded for interrogation, marching in socked feet across linoleum, counting the bolts on the shutter—show how ordinary lives are ground down by policy.

- A story of resistance that is quiet, stubborn, and deeply humane: the refusal to forget one's language, memories, or name.

- Meticulously crafted prose that feels both urgent and timeless, ideal for book clubs and readers of narrative nonfiction.

Perfect for readers of memoirs and human‑rights narratives who appreciate elegant, emotionally resonant storytelling—those moved by titles about political imprisonment, survival, and a family's fight to reunite.

Buy the book and start reading